A Creative Experiment in Passionate Non-Attachment.

WORDS AND IMAGERY BY STEVE CHAPMANSteve is an artist, writer and speaker interested in creativity and the human condition. He has sold work across four continents and exhibited alongside the likes of Pablo Picasso and David Shrigley. He has spoken around the world on creativity and is the host of Sound of Silence – the world’s first silent podcast, featuring special guests.

He is at his best when he is right on the edge of not quite knowing what he is doing.

For 91 days I was the founder and curator of London’s smallest and most visited independent art gallery. A claim I never thought I’d make, as somebody with no formal training or qualifications in art or curating. I never really intended to create the gallery. In fact, the whole thing came about through a series of experiments and ideas arising from the simple fact that I’m too much of a good boy to do graffiti.

I’m by no means the first person to have a free art project. I’m sure the concept of making art in order to set it free has been around ever since humans started walking upright. Although I appreciate cave paintings would have been far less portable in those days. But I came across the idea in 2011 when my friend, artist Gary Hirsch, started giving away Bots - small, unique robots- that he lovingly hand painted onto dominos. I’d long been a fan of Gary’s work and couldn’t believe he was giving away these beautiful things, releasing them into the wild with no idea where they would end up.

Sometimes he’d get an e-mail or a picture from somebody who had given them a loving home. Sometimes he would hear nothing, and the fate of the Bot would remain unknown for ever more. Free Art Fridays has grown to become a bit of a thing on social media.

My own free art project started in rather different way. I’ve always loved street art but -as I said- have always been too much of a good boy to spray paint on walls. I think this arose from seeing how much my grandparents were upset by the vandalism of their council flat. And whilst the older me can now see the distinct difference between vandalism and street art, I still couldn’t bring myself to do it.

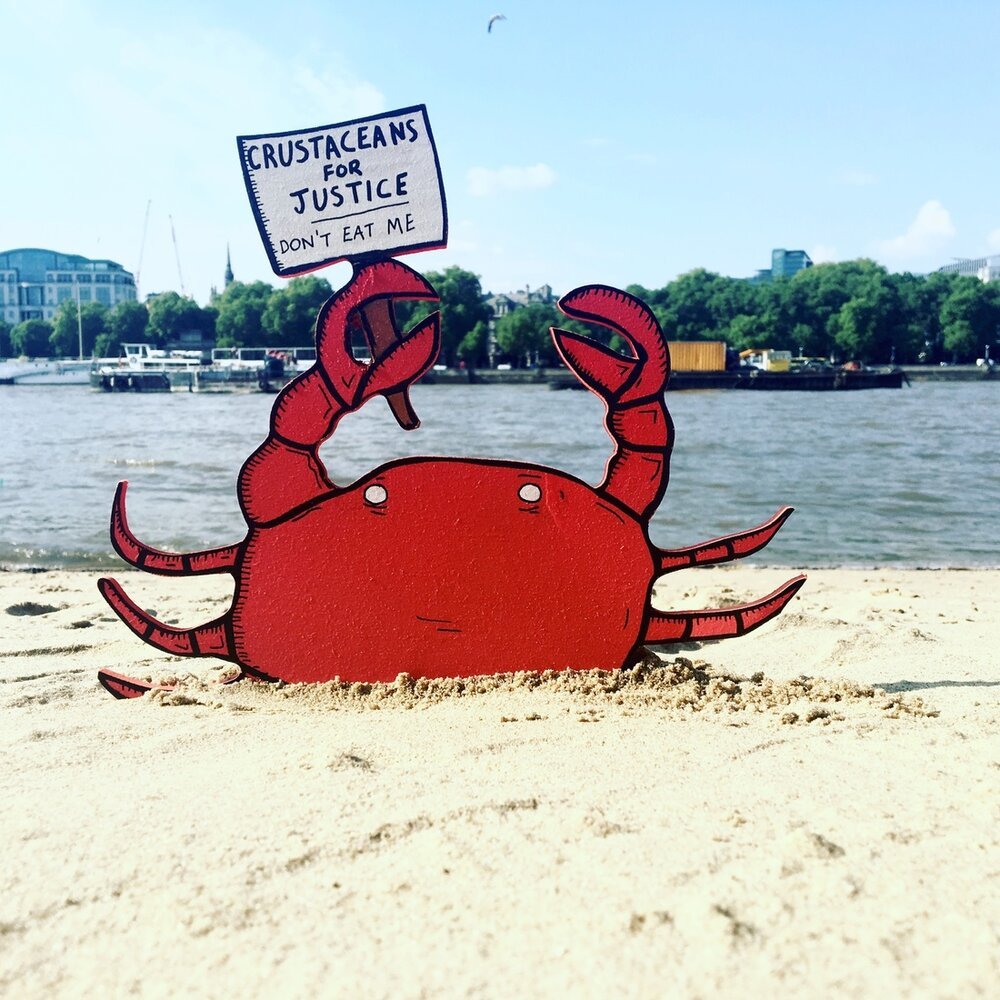

Then, one day in 2017 I came up with the idea of doing portable, impermanent street art. What if I painted pictures on bits of wood and stuck them on walls with blue tack? That way if somebody didn’t like it, they could remove it without the expensive costs of removing paint. But what if somebody liked it and stole it for themselves? The thought of this made me smile. That would be pretty cool actually.

And in that moment my own free art project began.

Since 2017 I have made over 300 unique hand cut, hand painted pieces of free art that I have set free in cities from London to New York, from Brighton to Berlin. Some pieces have been tiny, some huge. Some simple, some bloody complicated. Each piece has been lovingly made at home on my rickety old scroll saw and freed for members of the public to find. Often I add my Instagram handle to the back of the pieces as it’s lovely to see where the pieces end up but quite often I’ll leave no contact details to fully experience what it is like to let go of something one loves.

It is as much of a philosophical experiment in impermanence as it is a way of getting my art seen.

The project grew in many delightful ways. A few pieces have been found in places where I didn’t leave them! One piece I left in Covent Garden was found in an abandoned monastery in France. The finder said they were going to re-release it into the wild when they returned to Japan. I brought a batch of pieces to The Good Life Experience festival and hid them around the site, posting clues on social media to where they were hidden.

I spotted a number of pieces with their new owners making new friends and even spotted a piece dancing at the Snapped Ankles gig one evening.

On another occasion I created an impermanent art exhibition/treasure hunt as part of the Outsider Art Festival in Deal, Kent. Hiding 20 pieces throughout the town and watching as people literally ran in packs to try and find them. I started to hide the pieces in local shops; getting the shop owners to set a challenge in order to claim the piece, resulting in loads of people visiting and -even if they didn’t get the piece- buying food/music/art and meeting other hunters.

In early 2019, I had the idea of doing the opposite. What if I created something and left it somewhere as a permanent installation? What would that feel like? I set about thinking how I could make something that was both permanent and impermanent at the same time and whilst walking over the Golden Jubilee footbridge in London I spotted it. A dilapidated old concrete plinth on the side of Hungerford Railway Bridge that was level with the footbridge.

I’d tried the previous year to install something on one of the lower plinths but, as I watched the piece float off down the Thames, I realised that it was impossible to install with any degree of accuracy.

But this higher plinth, with its cruel looking anti-climbing spikes, would be perfect for some large wooden pieces. If I was able to find a way of getting a piece over the 6-foot gap between the bridge and the plinth it would likely remain there for some time.

I headed home and made a large piece featuring Len, one of my recurring characters, and modified an extendible washing line pole to help me place the piece onto the plinth. On Sunday 2nd June 2019 I got the earliest train I could into London and installed it. A week later Len was still there. And even though a few people seemed to notice he was there, he looked a little lonely. I thought I should probably add another piece to keep him company. Or maybe a few pieces. It would look like a gallery.

A gallery!

The following Sunday I returned with Don and The Naturist and a sign claiming the plinth to be The Hungerford Bridge Gallery of Outsider Art (#HBGOA). I’ve long been frustrated at the rather elitist art intuitions in the U.K. and the severe lack of outsider art on display, so this was my own two fingers up to the establishment.

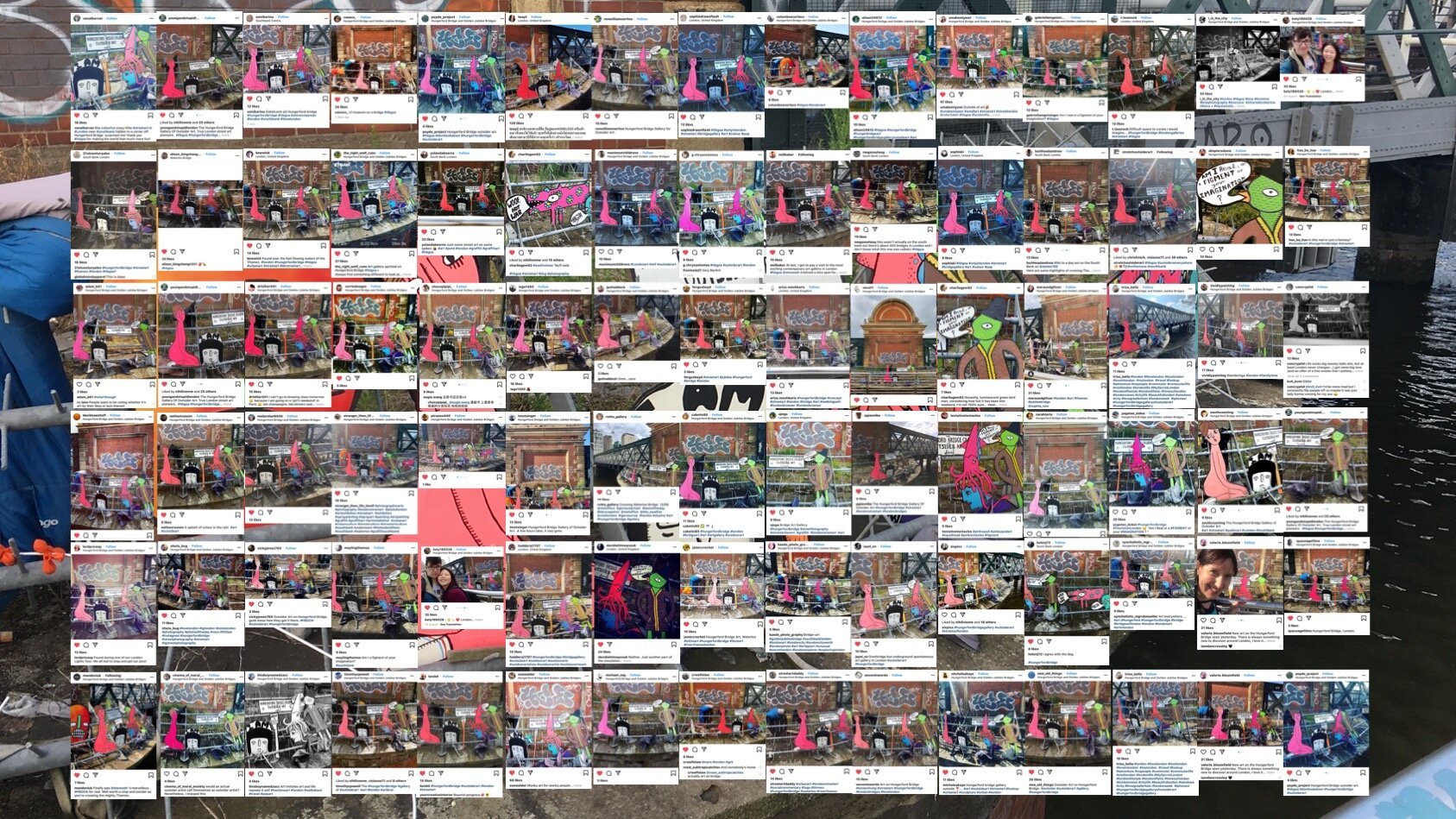

Over the next week I started to notice a number of social media posts about #HBGOA. “Brightens my day.” “A subversive little treasure”. “A splash of colour in the London grey.” It seemed that people liked it. Or were at least noticing it.

When I next walked across the bridge, I spotted crowds of people stood around the gallery taking photos; looks of joy and utter confusion on their faces. Over the next few Sundays I added the final pieces: Lady Squidhead, The Hand of HBGOA, Peace Dog, Extinction and The Head of HBGOA. The crowds grew and as did the social media posts: “Lovely to see squid lady joining the family”.

HBGOA became a pattern interrupter of people’s routines. Something I hadn’t intended but something I very much liked. People would slow down to look. They would stop. They would notice. Smile.

Even the most buttoned down be-suited commuter rushing over the bridge seemed to look at it warily from the corner of their eye. And, as between 8,000-11,000 people cross the bridge every day I decided that I could now claim that HBGOA was London’s most visited independent art gallery.

On the 31st August 2019, 91 days after I had installed Len, I spotted a post on Instagram saying that #HBGOA had vanished. I jumped on a train to see for myself and it was true. The plinth had returned to its dilapidated form of twisted metal, litter and abandoned sleeping bags.

I never found out the final fate of HBGOA other than it had been removed as part of the Westminster council efforts to “tidy stuff up.”

I like to think that a council worker somewhere has them on display in his living room although I suspect they ended up in a skip. Many people have asked me if I am upset at its fate and the answer is always “no.” The very nature of street art is impermanent and I was delighted that it had actually lasted so long and been seen by so many people. Over time it probably would have lost its impact and, due to my impatience to apply varnish in the correct manner, probably would have started to rot and look awful.

To be honest, the fact that it was removed and presumably destroyed makes the story of HBGOA even more legendary.

Many spiritual practices believe that attachment is the cause of all human suffering. Our desire to hold onto things that we feel we need for only deepens our fear and anxiety of losing them. The free art project has helped me to practice passionate non-attachment. To be passionate in creating the pieces but equally OK to let them go, knowing that I may never know their fate. 350+ experiences of micro-grief that get ever so slightly easier each time I say goodbye to a piece I have created. And that feels like a much less anxious way to live whilst brightening up the day of those who stumble across these weird, brightly coloured bits of wood.

Not bad for a project that arose from being too much of a good boy to do graffiti.